First, I want to say how much I am looking forward to all the wonderful papers and panels introduced on this blog. Thanks to Ben and Jonathan for their tireless preparations of this virtual forum and our upcoming in-person discussions at the conference.

When I got the call for papers months ago, the title of our conference, “American Mythologies: Creating, Recreating, and Resisting National Narratives,” felt like a perfect way to think about a topic I’ve been working on as of late. I want to introduce to you (or remember them to those of you who have seen these paintings before) Palmer Hayden’s John Henry series (c. 1944-47), a collection of twelve paintings (plus two thematically-related works) that represent the life and death of that legendary hammer-wielding railroad man. In his attempt to translate a folk song he’d known since childhood into a series of epic cultural importance, Hayden was creating, recreating, and resisting national narratives.

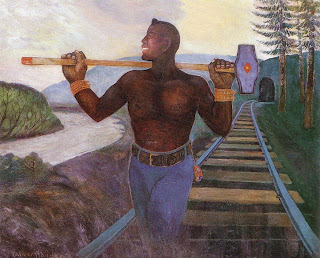

Palmer Hayden, His Hammer in His Hand

Hayden’s project was more ambitious than any previous visual iteration of the John Henry legend. Twelve paintings, in color, on a scale of approximately 30 x 40 inches each, dwarfed previous book illustrations and small-scale works on paper. Hayden’s research was unprecedented in scope; he read books, spoke with leading Henry scholars, and traveled to West Virginia two times to the site where Henry allegedly made his stand against the steam drill invented to replace human labor in railroad construction. Hayden came to believe that John Henry had actually existed, that he had actually challenged the steam drill to a contest, which he won, and that he had indeed perished after demonstrating his unsurpassed strength and fortitude. In these paintings, Hayden, an African American artist, sought to convey the reality of Henry’s life and his significance for 1940s Americans of all geographic and ethnic backgrounds. He attempted to create a national hero.

Palmer Hayden, Where'd You Git Them Hightop Shoes

In his efforts to create, Hayden also was recreating a story that so many Americans knew well from countless versions of a folk song. Titles like When John Henry Was a Baby and Where'd You Git Them Hightop Shoes reflect Hayden’s effort to incorporate lyrics and narrative details found in various versions of the song as a way to appeal broadly to Americans from diverse parts of the country.

The issue of resisting national narratives is more complex. It is an idea that I am still grappling with and one that I hope may elicit some discussion here and/or at the conference. I believe we can see Hayden’s series as an act of resistance against a national narrative of American heroes, which had been developing for decades upon decades, that neglected, minimized, undermined, or obliterated references to black folk heroes. Hayden’s insistence upon the actual existence of John Henry at a specific moment in history at a specific railroad tunnel in West Virginia (Big Bend, near Talcott, WV) and his repeated inclusion throughout the series of the patriotic red, white, and blue palette register as attempts to insert Henry into a national pantheon. His incorporation of white characters into crowds of onlookers and mourners, along with his depiction of Henry’s “woman” as white, may be further attempts to assert Henry’s applicability for a society that was grappling with issues racial justice and inclusion. All of this is complicated, however, by Hayden’s much-maligned figural style, which some viewers in the 1940s and since have found to resemble objectionable racial caricatures.

Hayden certainly believed in the heroism of John Henry and hoped his paintings would elevate and solidify Henry’s status in American culture. He sought, albeit unsuccessfully, to place his entire series into the collection of the Smithsonian. I look forward to examining these works and their context with many of you in November.

Lara Kuykendall, Ball State University

No comments:

Post a Comment